By John Clarke

Bringing the Dead to Life

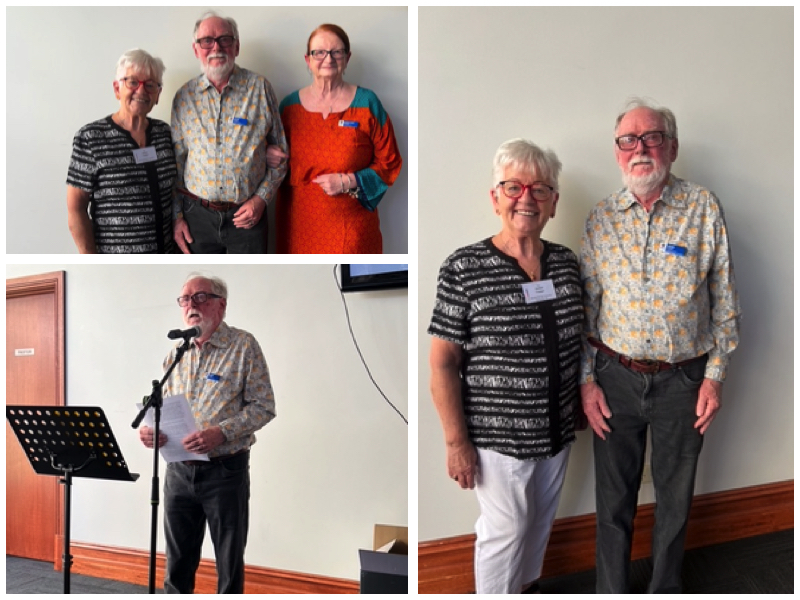

For many people today family history has become an obsession. At the last meeting of the German speaking group Kaffee und Kuchen I spoke about my approach to family history. My talk was entitled Living Ancestors.

I began by giving my definition of History: fact and speculation. My wife Kathleen is an amazing detective. (Without her there would be no Clarke family history.) She has scoured the internet, searching census and church records, and has provided the facts: ancestors’ names, place of birth and dates of birth and death. I have done the speculation, attempting to make of the ancestors living people.

Because of my audience I chose to speak of my German ancestors and first placed them in the context of their times. My great-great grandfather Mathias Sulzmann was born in 1809 in Sunthausen on the edge of the Black Forest, at a time when Napoleon was at the height of his power. Sunthausen was occupied by the French. Four years later, after Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia, the town was occupied by the Austrians. History gives an idea of the conditions under which they were living – humanizing them – but what of the people themselves?

Occupations give a clue. Mathias’ father Johann was a Landwirt (farmer), his oldest son Johann was a doctor, and Mathias himself was a clock and watch maker. And there was a half sister named Euphrosyne. (Euphrosyne was one of the Greek Graces, goddess of merriment and mirth.) Clearly the Sulzmann family had received some education.

Sunthausen Catholic church records show that Mathias emigrated to America. He lived there for five years and probably became a committed Baptist (important for my speculation; it is certain that he was a Baptist when living in the Barossa Valley).

My great-great grandmother Amalia Bertha Schubert was born in 1827 in Wüste-Waltersdorf, Silesia, an even more troubled region. Oppressed by the Prussians and the weaving industry in chaos – the majority of the village’s inhabitants were weavers – many chose to leave. Friedrich Wilhelm Schubert with his wife and daughter, mother and sister sailed for South Australia aboard the Victoria in 1848. Friedrich Wilhelm was not a weaver – he was a blacksmith – and he may have emigrated to escape religious repression.

How did Mathias and Amalia Bertha meet? He was a clock and watch maker in Gawler, and she was a blacksmith’s sister in Tanunda. Was there a market for his goods in Tanunda? Did he go there to converse in his native language? Simply asking the questions makes them more than names and dates on a family tree.

And there are more questions. Why did Mathias and Amalia Bertha marry at St George’s Anglican Church in Gawler? Why did he give his age as 38 when he was 41? (She was 23.) The marriage certificate records the official witnesses, including the Barossa Valley’s first entrepeneur Charles Young (Carl Jung), but where are the names of Amalia Bertha’s family members? And when they had children, why were none of those family members listed as godparents?

Did Friedrich Wilhelm object to his sister’s marrying an older man, a man who was not a Lutheran? Was there a permanent rift in the family? Friedrich Wilhelm became an Elder of the Langmeil Church, but despite living in Tanunda the Sulzmann family’s association seems to have been with Bethany people.

Was Mathias a doting husband? He must have agreed to Lutheran baptisms for his children (though they like their father grew up to be dedicated Baptists). And when Amalia Bertha died in 1857 after giving birth to their third child, the daughter was given her mother’s name. And although he was not yet fifty, he did not marry again. But there was no headstone erected in her memory in the old Bethany Cemetery.

Family Bibles provide information and also invite speculation. Mathias recorded information about his wife and children, his father, his brother Anton, who had settled at Greenock, and Baptist friends, but there is nothing relating to the Schubert family.

To end my talk I presented a breakdown of my DNA. (27% Germanic Europe) Surprisingly, as my mother’s maiden name was Cassidy, I have only 2% Ireland. By far the highest is 44% Scotland. That surely invites speculation.

In 1603 Queen Elizabeth I died. She was succeeded by her nephew James, the King of Scotland, who became James I of England. James knew he had a problem Along the border between England and Scotland there were unruly people, known as reivers. He decided to give the reivers land in recently conquered Ireland, making of unreliable subjects grateful friends. Many were settled at Killybegs in north-western Ireland, the home of my Irish ancestors. Speculation concocts a love story: an Irish Catholic man named Cassidy falls in love with a newcomer Scottish Protestant girl, and they marry, separating him for ever from his family. Their children find spouses among the Scottish community, generation after generation, right down to my grandfather Thomas Cassidy, a proud Orangeman.

Speculation does not provide proof, but it gives life to the ancestors.

The next Kaffee und Kuchen meeting will be held at the Langmeil Centre, 7 Maria Street, Tanunda on Monday, 31 March, starting at 1 pm. It will be preceded at 12 noon by a German luncheon ($25 per head). Those wishing to attend should contact Steffi Traeger (0408 621 384).